Tel +44 (0) 7764 165300 - Order by Phone / Online

You have ( 0 ) item(s) in your basket

Tel +44 (0) 7764 165300 - Order by Phone / Online

You have ( 0 ) item(s) in your basket

Code: JR1423

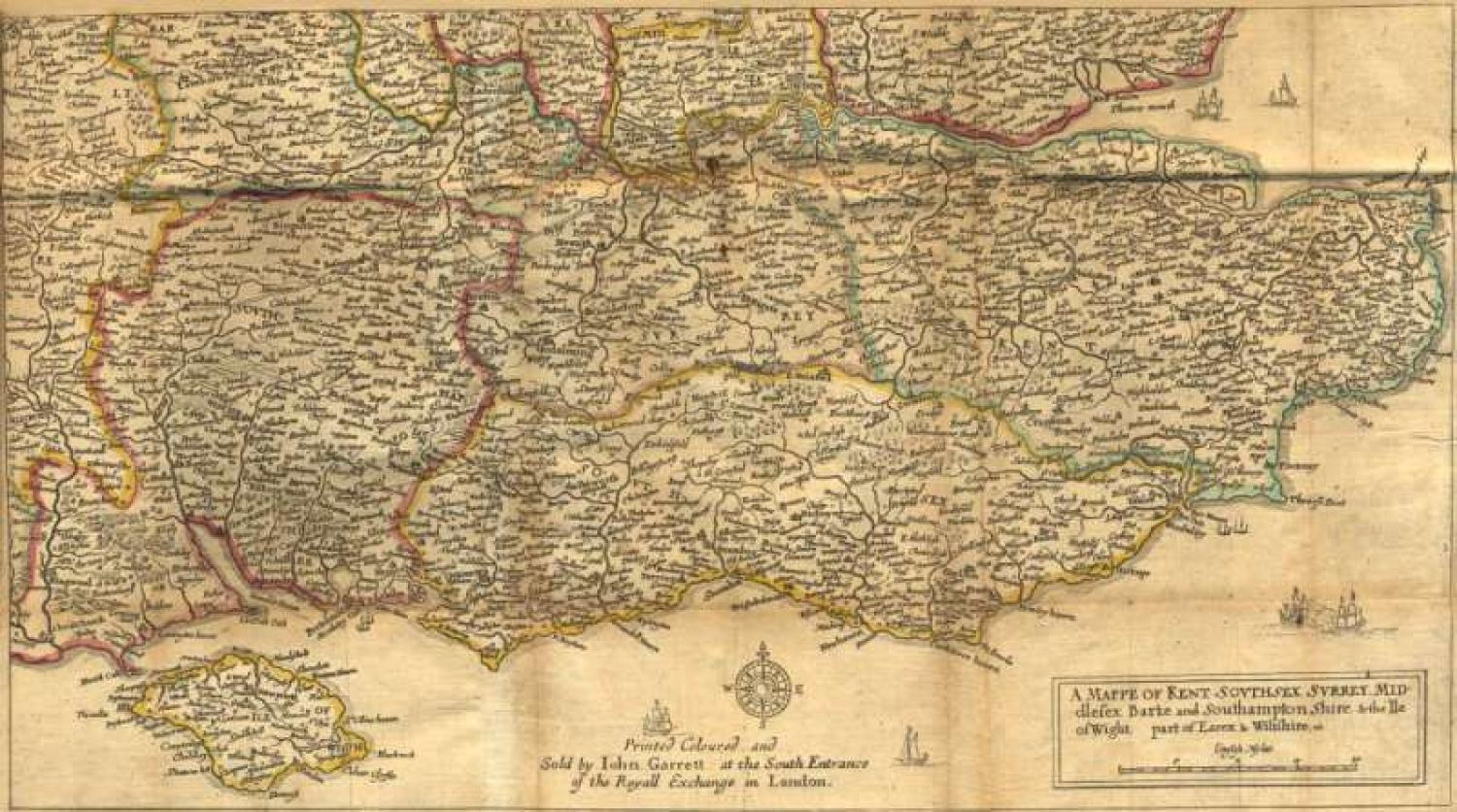

Title: 'A Mappe of Kent, Southsex, Surrey, Middlesex, Barke and Southamptonshire and the Ile of Wight, part of Essex & Wiltshire, etc'.Â

withÂ

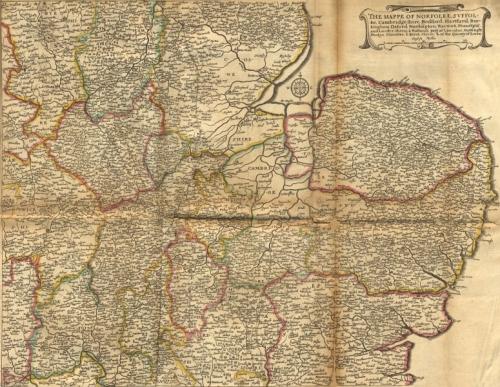

The Mappe of Norfolke, Svffolke, Cambridgeshire, Bedford, Hartford, Buckingham, Oxford, Northapton, Warwick, Huntingto and Lecestershires & Ruthland, Part of Lincolne, Nottingh, Darbye, Glocester, & Barck Shires, & of the County of EssexÂ

PROVENANCE: "The Kingdome of England & Principality of Wales exactly described whith every sheere & the small townes in every one of them"; Printed by John Garrett, London.Â

Two sheets of the Quartermaster Map, by Wenceslaus Hollar, based on the large wall map of England and Wales, 'Britannia Insularum in Oceano Maximo' by Christopher Saxton, 1583. Printed Coloured and Sold by John Garrett at the South Entrance of the Royall Exchange in London.Â

This work is better known by its later name, the " Quartermaster's Map," and was a close copy, cartographically, of Saxton's general map of England and Wales of 1583, and shows rivers, bridges, lakes, towns and principal villages. On the left, the title and scale in an ornamental cartouche. A single line forms the border. Jenner reprinted the maps in 1671, by Garrett in 1676 and 1687, and by J. Rocque in 1752.Â

J. Rocque, when publishing the reprint in 1752, stated that the map was originally produced at the orders of Oliver Cromwell, for the use of the Parliamentary Army. Sir H. G. Fordham, however, considered it was produced simply as a commercial venture of Thomas Jenner to meet an emergency demand, as he failed to find any foundation for Rocque's statement. (Source: David Hulse).Â

The condition of the Kent map is very good with original outline colour, on linen. The map is creased, with a 25mm tear along fold in the centre of map and a small hole approx 10mm long. Minor spotting and minor blemishes. The scale about 6 miles to 1 inch.Â

Â

The Norfolf map is creased; 11cm tear along fold at bottom; wear at junction of folds. Tight bottom margin below caption. 15.5 x 20 inchesÂ

Editions of this map:Â

Map by Wenceslaus Hollar, published by Thomas Jenner, London, 1644;Â

Published again by Thomas Jenner, 1671.Â

Published with roads added, by John Garrett, Royal Exchange, London, 1675 on silk, 1676 and 1688.Â

Published by John Rocque, London, 1752 and 1759Â

Background to this map:Â

Chorographic or topographic writing was uncommon during the Civil War. Popular during the previous decades, the kind of generic categorisation of the nation seemed to serve little polemic purpose and have no audience during this period. However, the mapping or description of national space became increasingly affected by the war, as can be seen for instance with the publication in 1644 of Wenceslaus Hollar’s Quartermaster maps. Intended for widespread popular usage, the engravings were divided into six easily digestible sections of landscape, mapping the conflict in ‘English Myles’ onto the physical body of the country. They reflect the fragmentary nature of the war, and are importantly Parliamentarian insofar as they do not overtly acknowledge the King’s presence in their precise visualisation of the country. The lack of royal crests on the maps implies that they are disassociated from the King, despite monarchical involvement in nearly every aspect of English topography, from Royal charters for cities to Royal boundaries for counties. Furthermore, the lack of coats of arms is quite deliberate, as they do appear on Saxton’s original versions from which the maps are copied. The configuration and topographic categorisation of England was therefore becoming an important political issue. Hollar’s maps construct a nationhood united through a common land but divided into regional identity; a nation, furthermore, with little need for a centralised notion of a King but rather a Parliament that ‘blended together the overlapping and ambiguous notions of “the countryâ€, ranging from neighbourhood to commonwealth.’Â

Source: Oxford University Press.